Accessible Hardware Accelerated Graphics (and WebGL)

Hardware accelerated graphics have a variety of challenges related to accessibility and in this lesson you will go over them

Overview

The use of hardware accelerated graphics is common and making them accessible is possible with some effort. How to accomplish this varies by platform and in this lesson, you will learn an approach for making graphics-based web applications accessible. Traditionally the canvas element provides a way to render graphics through the Canvas API or through WebGL. There is no default way to convey any structure or text for assistive technologies. This lesson will give you an understanding of one method to try to close that gap in accessibility by creating a parallel layer of accessible DOM elements called a shadow-dom. The goal of this method is to expose canvas-based content in a way that supports accessibility while remaining graphical and universally designed.

Goals

You have the following goals for this lesson:

- Understand the accessibility limitations of the HTML canvas

- Learn about the shadow-dom

- Understand how semantic HTML elements and ARIA attributes can provide meaning and structure to a canvas

- Learn about accessible starvation inside of graphics applications

Warm up

All graphics in a computer have the concept of frames of animation. In some cases, these frames are hidden from you. In some graphics applications, however, you can control them. How do you think frames of animation impact accessibility systems?

Vocabulary

You will be learning about the following vocabulary words:

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Document Object Model | A data representation of the objects that make up a web page. This representation provides an interface so that programs can change and view the web page’s structure, style, and content. |

| Accessibility Tree | A structured, hierarchical representation of a user interface that is exposed to assistive technologies. It is built from the underlying UI elements and reflects only the parts of the interface that are relevant for accessibility. |

| shadow-dom | DOM elements created in parallel to a graphical application to present the objects in the graphical application in a way visible to assistive technology. |

| Accessible Starvation | An issue that arises due to graphics, user interaction, and accessibility messages at a low level entering a shared message queue. Messages from any aspect of the application are shared in this queue and thus interleaving issues like frames of animation can interfere with and cause significant delays with assistive technologies. |

Web Content Accessibility Standards

This lesson covers the following standards:

- WCAG 2.2 - 1.1.1 Non-text content

- WCAG 2.2 - 1.3.1 Info and Relationships

- WCAG 2.2 - 2.1.1 Keyboard

- WCAG 2.2 - 4.1.2 Name, Role, Value

Explore

Graphics is a crucial aspect of computer science. To say that the number of applications of graphics, from movies, to games, to serious applications of computer aided design or visualizations in programming languages, is to undersell it. Even on the web, interactive content often heavily makes use of graphics. There are many ways to do it and they all need to be managed differently. For example, one on the web is using the HTML canvas element. The canvas is an element that provides a space where you can draw graphics using JavaScript. Some complex applications make use of WebGL which enables high-performance interactive 2D and even 3D graphics. This might sound impossible for accessibility, but is not.

The canvas element allows you to draw various shapes, text, and images, but it presents a complex accessibility problem. When it comes to this kind of rendering, assistive technology like screen readers do not understand what the pixels represent and it effectively creates a black box to users that do not rely on visuals. Further, frames of animation are interleaved in complex ways with accessibility events and if care is not provided, you can quickly run into a phenomenon called accessible starvation. Accessible starvation is the phenomenon where the graphics system proceeds faster than the accessibility system, which can make the accessibility system feel slow [1].

Past starvation, accessibility systems do not work by interpreting pixels. They work instead through structure and descriptions of that structure. A canvas might display a meaningful user interface, but with no structure or attributes attached to the elements on a canvas, it is effectively invisible to accessibility systems. A user interface built on a canvas also does not have keyboard navigation built into it. Again, without additional work, anything drawn on a canvas is essentially invisible to accessibility systems. Making these systems accessible is harder than just setting a tag, but important for universal design.

Certain kinds of applications make good use of the flexibility and performance advantages of the canvas. Some of the use cases could be custom games, educational tools, rich data visualizations, or paint applications. Even with the challenges to accessibility the canvas does not need to be avoided. With a complementary meaningful and accessible representation the canvas can be made accessible. For this, you need to understand the Document Object Model and the shadow-dom.

Document Object Model

To understand how a canvas can be made accessible you need to understand how assistive technology interprets a web page. This is where the Document Object Model (DOM) comes into play. The DOM is a data representation of the objects that make up a web page. This representation provides an interface so that programs can change and view the web page's structure, style, and content. The DOM is the core reason why a user that can see can see a web page. However, while less obvious, many kinds of accessibility devices interpret it in unique ways, allowing users to see, hear, or touch it.

As mentioned previously, accessibility systems have an underlying accessibility tree, which is translated from the web into native components at the operating system level. The accessibility tree is a translation of the DOM that includes information that helps understand the content of and functionality of a page. This includes:

- Element roles (e.g., button, heading, list item)

- Accessible name or label

- State and properties (e.g., checked, disabled, expanded)

- Focus order

- Relationships

When an element makes use of semantic HTML or different ARIA attributes, it becomes part of the accessibility tree. If there is no applicable role and has none of the information mentioned above (like a canvas) it will be invisible or meaningless to accessibility systems. By all rights, it does not exist. This disconnect between the accessibility tree and what is on the page visually is where interfaces can fail to be accessible. This also belies why WCAG is both helpful and not. WCAG provides a sense of some rules to follow, but gives arguably minimal or no guidance on how to manage issues with graphics.

Bridging the Gap

To ensure canvas content is usable for everyone it is possible to create an accessible equivalent to what is on the canvas but visible to the accessibility tree. This strange approach has a funny name: the shadow-dom. The shadow-dom is a practical approach to providing structure in a hidden, semantic HTML version of each meaningful object drawn on the canvas. While the HTML elements would not appear visually, they show up in the accessibility tree and can thus be manipulated.

While ARIA roles and attributes are important for accessibility they cannot create interactive elements on their own. Consider an example of a graphical button.

Visually there is the text 'Click me!' surrounded by a rounded rectangle. Now on a canvas, this is just pixels. However, all a button is, when you think about it, is pixels drawn on screen with some information under the hood on what those pixels mean. This is true visually, has affordances with input devices, and is easy to understand. What this means is that if you can mimic the behavior of a button, you can draw whatever you wish, give it whatever affordances you wish, and accessibility devices will interpret this however you wish. All of a sudden, you can control a canvas from the perspective of universal design.

To actually do this, you need an accessible representation that includes:

- HTML element

- Accessible Name

- Role

- States or properties (if appropriate)

For this graphic HTML already has a button element and you can try to fill in the rest from there. The code for a semantic equivalent might look something like this:

<div id='container'>

<button id='bttn'>Click me!</button>

</div>

Or you can use roles and ARIA attributes instead:

<div id='container'>

<div id='bttn' role='button'>Click me!</div>

</div>

The big difference between the two code examples is the browsers add functionality to the <button> element whereas the approach using only <div> elements would require that you create the functionality of a button in JavaScript manually. Whether you do it one way or another depends on what you are building and its purpose. A fire breathing dragon eating a garden gnome that is clickable might have slightly different affordances than this button.

Now if you were to add that code might be something like this:

<div id='container' style='position: relative;'>

<div id='bttn' role='button' aria-label='Click me!' style='position: absolute; left: 200; bottom: 200; width: 75; height: 25'></div>

<canvas aria-hidden='true' width='500' height='500'>

</div>Now, you might have noticed there were some extra attributes added compared to the previous example. For one, the canvas has the aria-hidden attribute. While the canvas is the main object controlling the UI, when you have an accessible equivalent to what is on the canvas, the user does not actually need to be able to observe the canvas in the accessibility tree. All the user needs to know is that there is a button they can click and adding the canvas to the accessibility tree would only add an extra element that could confuse the user. Also notice that the button is parallel to the canvas, not under it. This is not an accident and why it is necessary is complicated, but generally elements are in parallel. Thus, you have created a parallel shadow-dom.

There is also extra style information added to the button. There are attributes related to position, location, and the like. These should not be ignored and are crucially important to be in the accessibility tree. Remember: these properties are used across many technologies and used by many disabilities. Not having them breaks universal design and, in this particular case, counterintuitively would also break screen readers, which require bounding box information. If you are rendering in 3D, this means all graphics need to translate to screen coordinates with standard transforms that are outside the scope of this lesson.

Mapping Accessible Equivalents

The previous example only had a single button so the accessible equivalent was pretty straightforward. As canvas graphics get more complex there is more to consider.

Keep in mind that not everything drawn to a canvas needs a semantic equivalent. With the power of complex graphics and animations some content might purely be decorative and will not provide any meaning or understanding to a non-sighted user. You do not need to just duplicate the content but take a thoughtful consideration of the roles, the relationships, and the user experience.

Focus on content that:

- Conveys meaning like labels or data points

- Offers interactivity like a button or a slider

- Responds to input or gives feedback like a selection indicator or an alert

A decorative background pattern does not need an equivalent but a chart legend might. Structural relationships might need different information. If the canvas has a user interface separated into different groups then using div elements with a 'region' role might be helpful to group parts of the interface together. Grouping elements can also have an impact on switch controls.

Interfaces can also be dynamic, so it is important to keep the equivalent DOM in sync with what is happening in the canvas. This includes changes to the focus, state updates, and keyboard interaction. This approach of creating an equivalent DOM might affect the interaction model of your canvas application because now the user is actually interacting with a DOM object instead of whatever handlers you might have made custom for the canvas. Because of this it is important to hook up certain events like the button's onClick for example to connect to your application. This will vary between implementations but the idea is to use javascript event listeners to ensure DOM actions update the canvas, and canvas actions update the DOM.

It is also important when using this approach to test with assistive technologies and inspectors to make sure the equivalent you create works how you would expect. Inspectors can verify that names and roles are correct and verify that the element is visible to assistive technology.

Mobile Considerations

While creating a shadow-dom is a powerful technique for improving canvas accessibility on desktop environments, applying it effectively on mobile devices introduces unique challenges. Mobile screen readers like VoiceOver (iOS) and TalkBack (Android) rely heavily on touch-based interaction, gestures, and rotor-based navigation instead of the keyboard-based focus models used on desktops. And as an added challenge, not all of the input events are passed the same when a mobile screen reader is on. In other words, the application designer does not get the same information as you do on desktop, which makes it difficult to give users an equivalent experience for not very good reasons.

One of the key considerations is touch target discoverability. Mobile screen readers allow users to explore by touch. This means a user can drag a finger across the screen to feel the interface. However, if your bounds of elements are incorrect, they will not be discoverable via touch. They will still be available using swipe gestures like swiping left and right, but this can result in a non-intuitive, disconnected experience, where some users cannot spatially relate the content to what is shown on the canvas.

You can make use of the 'position: absolute' style property with relative containers above it to make sure items are positioned correctly. Another key consideration is the lack of input variety when a mobile screen reader is on. Typically mobile devices are not used with a physical keyboard attached. While there might be a software keyboard you might notice that it only really appears if you have to type text into specific areas, not for control like you would on a desktop. Because of this if you have keyboard shortcuts for a user to perform an action, a mobile user could lose access to that action.

To prevent issues with the lack of input variety there are multiple options. For one you can always create, as a part of the application, a button or other reachable component that performs the same thing. For example a map widget might let you pan around the move around the map. A mobile screen reader might not be able to pan because the touch input is used by the screen reader. You do not have to get rid of the panning to make the widget accessible, instead you can add buttons that move the map a certain amount and make those buttons reachable by keyboard and the normal focus order so a mobile screen reader user can find them.

To further help mobile screen reader users you can also add within the DOM implementation more hidden elements that would assist those users. For this method, you can add extra elements that these users might find helpful. Examples are headings since a common form of navigation is to move through the headings. These elements do not have to exist visually in the canvas, they can exist purely for mobile screen reader users so that they have a way to do equivalent actions possible on a keyboard or with normal gestures. Take this example HTML and pay attention to the <section> element:

<div id='container' style='position: relative;'>

<section>

<h2 style='position: absolute; left: 0px; top: 0px; width: 1px; height: 1px;'>

Canvas Options

</h2>

<button id='ZoomInBtn' style='position: absolute; left: 0px; top: 0px; width: 1px; height: 1px;'>

Zoom In

</button>

<button id='ZoomOutBtn' style='position: absolute; left: 0px; top: 0px; width: 1px; height: 1px;'>

Zoom Out

</button>

<button id='resetBtn' style='position: absolute; left: 0px; top: 0px; width: 1px; height: 1px;'>

Reset View

</button>

</section>

<div id='bttn' role='button' aria-label='Click me!' style='position: absolute; left: 200; bottom: 200; width: 75; height: 25'></div>

<canvas aria-hidden='true' width='500' height='500'>

</div>This is similar to a previous example but now there are 3 buttons grouped together under a heading. They are also styled to be tucked away in a corner so they are not discoverable by touch. If focus is also handled programmatically by the canvas application these elements should not be included. These elements are meant to exist within the accessibility tree but not interfere with non screen reader users. Mobile screen readers especially are difficult to read the inputs of for normal JavaScript applications. They also rely heavily on the DOM and the accessibility tree to navigate with screen reader gestures and this method provides options to give more functionality without needing more input methods.

At the end of the day, the point is that when programming for mobile, you have to be careful. Because, and in this case it is specific to screen readers, when a screen reader is turned on the browsers do not pass on all events, these hidden dom element structures are really one of very few options for accessibility. Honestly, this decision by manufacturers to effectively hide input events from browsers feels like it is either a bug or a serious design flaw. Despite this, workarounds like this at least provide some options.

Engage

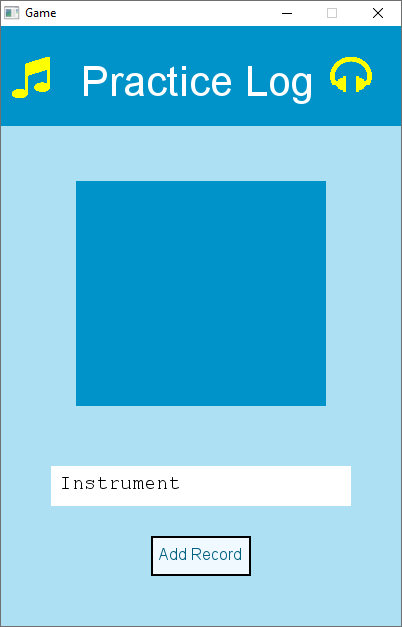

To be able to apply this to your own canvas applications you will need to be able to design your own DOM equivalents given a UI. For this activity you will be given a screenshot and you will need to design an equivalent DOM for it.

Directions

Examine the screenshot of a simple UI. Take note of all the different UI components you observe and think are important for a non-sighted user to know about.

Based on this screenshot, write up a mock DOM implementation for the UI. Use any HTML elements you know that you think would fit the UI. Do not just think about individual elements either, also think about how the structure is laid out too. Some example elements could be:

- button

- textarea

- label

- paragraph

- heading

- div

- section

This activity can be done as a group and the key is to think about the state, the properties, the roles, and other layers. Consider how you can make it accessible on mobile versus desktops and discuss in your group the options.

Wrap up

The HTML canvas is a powerful tool for drawing and interaction but it comes with a serious accessibility trade off. Because of the pixel rendering the canvas does not automatically have an underlying structure. Assistive technologies are not able to interpret or interact with content inside of the canvas by default, which can create a major barrier for some users. Mobile applications, especially, have different needs and considerations. For the graphics in your own application, consider how you might use shadow-doms for accessibility.

Next Tutorial

In the next tutorial, we will discuss Accessible Graphics within Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG), which describes how accessible Graphics can be done in a canvas, but also placed into Scalable Vector Graphics, with its own unique needs.