Web Content Accessibility Guidelines Section 3AA and 4AA

Understanding the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.2 AA

Overview

In these continued lessons on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, you will continue your journey through sections 3 and 4 AA. In these new standards, you will discuss navigation, errors, and status values. Past this, WCAG 2.2 has new rules around authentication that can be incorporated.

Goals

You have the following goals for this lesson:

- Learn what the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) are

- Learn specifically about 2.2 AA in regard to WCAG Sections 3 and 4

- Learn about new ideas for accessibility in WCAG 2.2 AA

Warm up

Imagine being tasked to read through a long set of online documentation for a new tool on an updated work policy. Consider how you would find specific information. You might rely on one of the following methods: a search bar to filter pages, a table of contents to direct you to the right section, or scrolling through and scanning the headings one by one. How do you imagine people with different abilities might navigate?

Vocabulary

You will be learning about the following vocabulary words:

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) | A set of standards about how to make content on the web accessible to people with disabilities |

| Cognitive Function Test | A task that requires the user to remember, manipulate, or transcribe information. |

| ARIA Live Region | This is a region of the page that can dynamically provide information about how a page is changing. |

| polite | A live region that tries to balance speed of updates and only do so when really needed |

| assertive | A live region that aggressively updates accessibility technology. |

Web Content Accessibility Standards

This lesson covers the following standards:

- WCAG 2.2 AA Section 3: Focuses on better input assistance and clearer error prevention than 3A, increasing understandability by requiring improved guidance, labeling, and error identification.

- WCAG 2.2 AA Section 4: Focuses on more compatibility with assistive technologies than 4A by insisting well-structured content and consistent behavior, supporting better interpretation by a broader range of user agents and tools.

Explore

The AA sections of WCAG in 3 and 4 are relatively light and need, arguably, less attention to figure out. At the heart of this area of WCAG is a simple idea, which is to leave things alone unless they need change. For example, imagine a website where on every page, there was a different navigation and layout. This would be annoying and all WCAG is really saying is not to do that. Of course, the real guidance uses different words, but the idea is pretty simple. As such, having consistent navigation and labeling is a big portion of this section.

Past the former, there are two different portions of WCAG that are interesting in this section, although they only apply in certain situations. The first is legal documents. Modern tools like DocuSign or others have signatures that are legally binding. WCAG is essentially arguing that some care should be applied when dealing with serious matters like banking or legal.

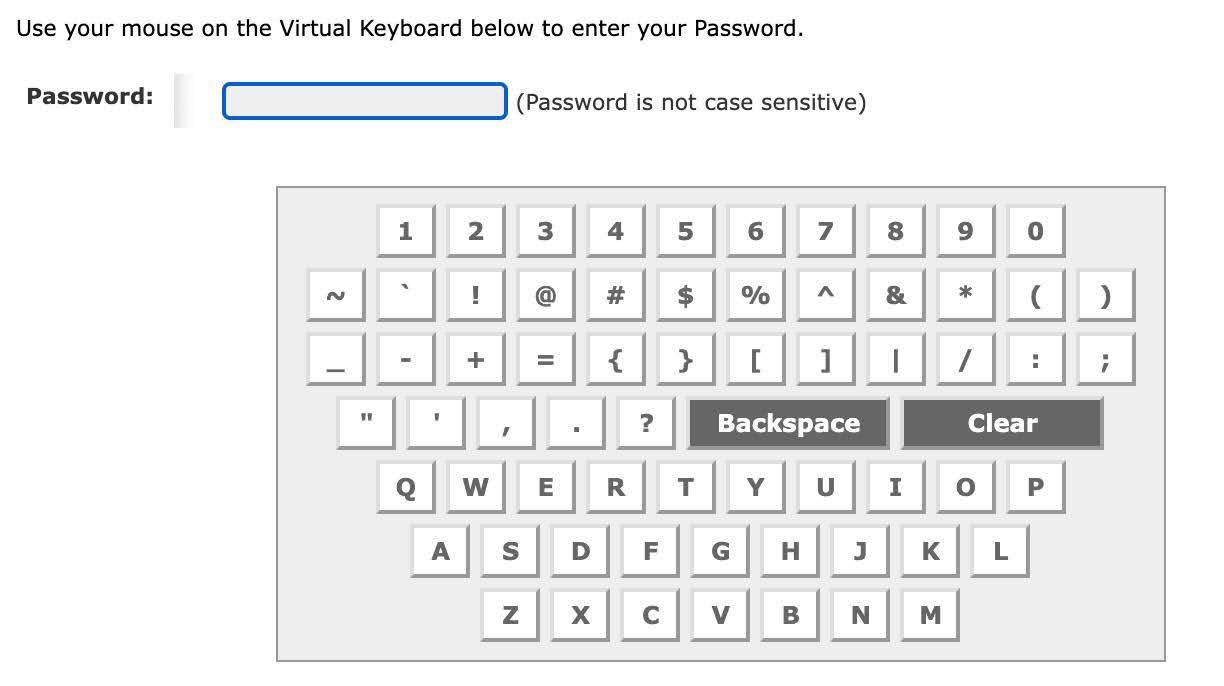

Past legal documents, section 3.3.8 is new to WCAG 2.2 and is on accessible authentication. Consider a tangible example related to authentication that seems to not just break this new rule, but so many others: the now defunct virtual keyboard from treasury direct. Treasury Direct is a website run by the U.S. Department of the treasury that for many years had a rather odd mechanism to log into its website. Notably, instead of a password field, it would display to the user a virtual keyboard where you type keys with the mouse.

Fortunately, the website did eventually remove this unfortunate design and this highlights again that accessibility is not just about people with disabilities. Yes, this system broke the website for people with disabilities in a variety of ways, but it does not take a convincing empirical study to grasp that this was a poor design for everyone.

As a secondary point, consider 3.3.8 in this context. In addition to many other WCAG rules, this violates this newer section because it breaks password managers. In other words, for your own work the idea is that you should not design a website where you make it difficult or impossible for tools like password managers to fill things in for users. In the very unusual instance where you might have to break such tools, alternative designs that remove the cognitive function test are important.

Section 3AA: Understandable

| Guideline | Description |

|---|---|

| 3.1.2 Language of Parts | If the human language of a part of the page changes, the language should be able to be programmatically determined |

| 3.2.3 Consistent Navigation | Navigation components like a navigation bar or search bar should be consistent across other pages |

| 3.2.4 Consistent Identification | Components that work the same across pages should be identified the same on each page |

| 3.3.3 Error Suggestion | If an error can be detected along with the reason for the error it should be stated to user unless that error would compromise security or purpose of the content |

| 3.3.4 Error Prevention | If content has a legal commitment or a financial transaction, it should either have reversible submissions, a way to check the data being entered, or a way to confirm information before it is finalized. |

| 3.3.8 Accessible Authentication (Minimum) (New to 2.2) | A cognitive test such as remembering a password is not required in any step for authentication. An example of this is allowing the use of a password manager or allowing email authentication. |

Past the bigger picture issues above, there are also some guidelines on errors. The key takeaway is that if there is an error, the user should get some idea about what to do about the error and how to prevent it in the future. In computer science, where things like compiler errors are common but not always easy to understand, keep in mind that perfect is the enemy of the good. These rules do not change the reality that mathematical limitations around errors may be real. It is just asking you to try and be reasonable about telling the user information they need.

Below is the rather short tablet on Section 4AA. This issue, one of robustness, is stating that status messages should be available programmatically. This is typically for tools like, but not only, screen readers because they may use these messages to inform the user in a way that is not visually obvious.

Section 4AA: Robust

| Guideline | Description |

|---|---|

| 4.1.3 Status Messages | Status messages should be able to be programmatically determined through roles or other properties. |

Consider an example related to the section 4AA criterion at Level AA. Status messages are messages that do not take you away from the content you are currently on, but provide information you may want to know. WCAG suggests using one of the roles, status or alert, but does not discuss the pros and cons of giving a dynamic attribute to a region. In fact, when discussing this issue with developers, a typical instinct is to put this information into what is called a live region.

An ARIA live region is a HTML element that notifies accessibility technologies about changes in the content of the element. Live regions are capable of alerting the user to any status updates, but not moving the keyboard focus.

Here is an example of a live region:

<div role="status" aria-live="polite">0 unsaved changes</div>Live regions also have a property that defines when changes are announced. A polite region, as seen in the example above, waits to announce a change until the screen reader finishes its current dialogue, whereas an assertive region announces the change immediately, even if it interrupts ongoing speech.

While it is important for users to be informed of changes in dynamic elements, this WCAG criterion does not provide guidance on when to use different types of live regions, nor does it address some of their potential drawbacks. Exactly the right approach is arguable, but caution is appropriate. Using live regions in general is appropriate sometimes, but sparingly is key. Further, only use aggressive ones if you have a very good reason. Even if you think you have a good reason, you should second guess whether it is really true.

Consider a more direct example. You might have visited a site with so much visual clutter that it was hard to understand. This same idea can apply to users who rely on touch or audio. If used incorrectly, a live region can trigger too frequently and become overwhelming. When you do need to announce an update, it must be meaningful, timely, and relevant, otherwise, it will create a bad user experience. In many ways, when and when not to use these and in what way is a judgment call.

Another consideration with live regions is that each screen reader may handle them differently. Timing, phrasing, and even whether the update is announced at all can vary between screen readers, operating systems and browsers. Braille devices, in particular, may differ significantly, as a dynamic update can be disruptive for a braille user. In a case like this, a live region might reduce usability, or the user might miss information that a screen reader user would have received. Put another way, even if you say assertive, it may not even work how you intend and what you intend may not make sense anyway.

Engage

Now that you have more knowledge about all 4 sections of WCAG an important skill to have is to be able to identify any accessibility issues on a page. It is important to be able to identify problems from source code but also from the perspective of use. After all, users typically do not open up the developer console when they visit a new page.

Directions

You will next examine two web pages. These web pages are intentionally designed to violate certain aspects of WCAG for educational purposes. One page is highlighting a whole host of errors. For this page, try to navigate the page examine the source code of the page and try to imagine how it should be adjusted. Keep these questions in mind while you evaluate the page:

- Can you navigate the page?

- Does the navigation make sense?

- Are components clearly labeled?

- Do the labels make sense?

- Is it clear when there is an error?

- Is it clear what element is focused?

- Are there any images that convey information but lack alt text?

The inaccessible page can be found here.

The second page is designed to highlight ARIA live regions with different tags. For this one, consider using a screen reader and multiple browsers. Then, ask yourself the following questions:

- When do you think it might be appropriate to use live regions in general?

- How do different browsers react when using polite or assertive live regions?

- What kind of issues do you think you need to watch out for with live regions and browsers?

The live region demonstration page can be found here.

Wrap up

WCAG provides a baseline for what it takes to create content that is accessible and inclusive. From making sure that keyboard users can navigate, to readable text, and meaningful feedback. Remember that while reading these guidelines that while it might be a legal requirement, accessibility is also about designing with empathy. Meeting these criteria do not just help people who are blind, they help everyone.

Next Tutorial

In the next tutorial, we will discuss No-Mouse Practice, which describes practicing and understanding keyboard only navigation and exploration.