Hour 2: Block Programming, Text, and Booleans

This lesson is to teach you about text and boolean values.

Overview

As you grow, you learn many different facets of natural languages. Depending on the culture and geographic region you grow up in, this might be English, Spanish, French, or many other languages. This may also include parts of a language you know, like how science or math is described. Programming languages are in some ways very similar, and in other ways very different, from natural languages. You use a variety of words to represent concepts, but in computers they are more picky and also more exact. In this lesson you will be using words like text and boolean, then sending them to your very picky friend: an online coding environment called Quorum Blocks. This online tool will let you edit and run your programs.

Goals

You have the following goals for this lesson:

- Learn the basic keyboard and mouse operations for using blocks

- Learn about blank blocks

- Use the the text and boolean types

- Learn about accessibility devices with block programming

Warm up

Imagine two possible ways of learning English as a second language. In the first, you receive a list of words on a piece of paper and their definitions in another native language. You then memorize the details and try to link it in your mind. In the second, this list of words is on the computer and can adapt to what is already on the screen as you go. The computer decides what words can be used and when. Traditionally, this is the distinction between text-based and block-based programming. What do you imagine are the pros and cons of both approaches?

Vocabulary

You will be learning about the following vocabulary words:

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Block programming | Block programming is a style where visual blocks represent pieces of the computer code that can be manipulated through various forms of user input. |

| Block Tray | A region in a visual editor that contains information about the code in the editor |

| Block Editor | A region in a visual editor that contains all of the lines of code in a user's program. The editor can be manipulated with the keyboard, the mouse, or through the block tray. |

| text | Text is any combination of written symbols, like letters or numbers. |

| boolean | A boolean variable can be only true or false |

| Variable | A variable is a storage container. It has a name, a data type, and a value. |

Code

You will be using the following new pieces of code:

| Quorum Code | Code | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| say | say "hi" | A command that talks out loud through the computer's speaker |

| output | output "hi" | A command that sends text to the computer's console |

| text NAME = VALUE | text string = "hi" | Creates a new variable called NAME that can store text, and puts VALUE in the container. |

| boolean NAME = VALUE | boolean bool = true | Creates a new variable called NAME that can store booleans, and puts VALUE in the container. |

CSTA Standards

This lesson covers the following standards:

- 3A-CS-01: Explain how abstractions hide the underlying implementation details of computing systems embedded in everyday objects.

- 3A-CS-02: Compare levels of abstraction and interactions between application software, system software, and hardware layers.

- 3A-AP-17: Decompose problems into smaller components through systematic analysis, using constructs such as procedures, modules, and/or objects.

Explore

Visualization and graphics have become a hallmark of how students learn to code. Traditional approaches that make use of graphics vary and include ideas like drag and drop, animated characters, scientific visualization to represent data, 2D or 3D game programming, or many other ideas. This can be fun, compelling, and interesting, but has historically had one clear flaw: they were not always accessible to people with disabilities. In this exploration section, you will be exploring and tinkering with an online programming environment (IDE) designed with a new design philosophy sometimes called Accessible Graphics. While the term can be interpreted in many ways, in this context the big idea is to keep the graphics and the fun, to the greatest extent that is reasonable, and be as inclusive as possible.

Before thinking about how to use such environments, it helps to consider whether block environments should be used at all. After all, professional programmers, near exclusively, use text and only text based environments to code. Beginners, typically in or before high school, tend to use so-called 'block' environments. A common block environment students may have been previously exposed to would be MIT’s Scratch, although there are many others. The bottom line in academic research is that block environments do tend to help people learn, but those gains tend to be small and rather short lived [2]. Students typically use them only for a few weeks. Further, if that learning is freeform, meaning students tinker with minimal or no guidance, it may not lead to positive learning outcomes [1]. Put another way, blocks are somewhat helpful to learners, but they are not magic and students need direction.

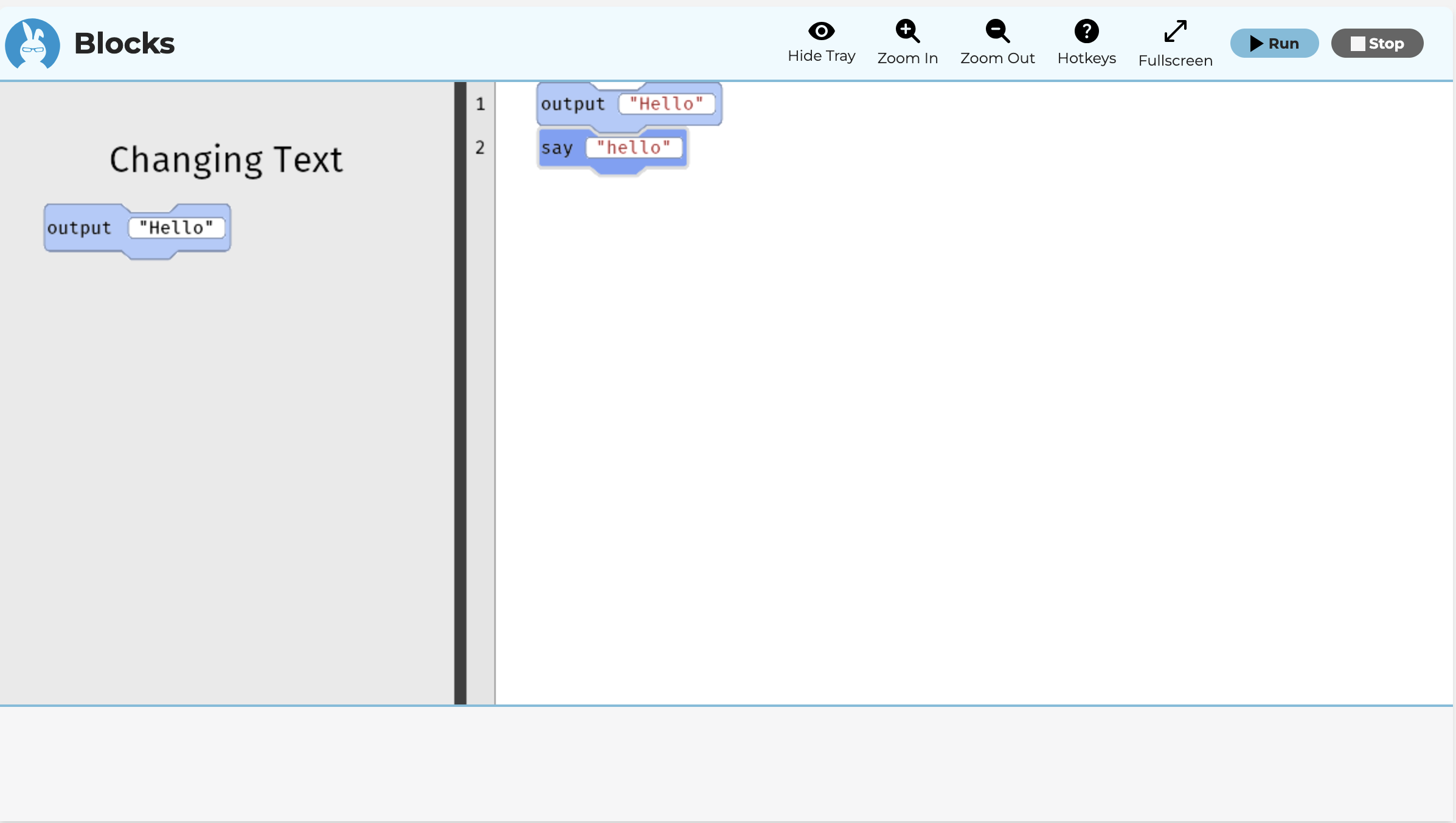

In this explore section, the next step is to think about how to use blocks. You will explore, optionally, using several possible affordances, including the mouse, the keyboard, and a screen reader and will continue to use online coding tools. As a first step, consider what happens if you drag or use the keyboard to put multiple blocks into the environment, including at least one that has a beginning and an end. Here is an example of an output and say statement. This might appear as follows:

The Double Cursor

When using blocks, there are multiple ways to interact with the environment and the crucial one to understand is called the double cursor. Typical text editors have only one cursor, which is vertical, but block environments sometimes have two, as shown below:

The vertical cursor exists inside of individual text fields or text boxes. The difference between a text field and a textbox is that text fields must be only one line. Textboxes can have multiple lines. The horizontal cursor indicates the line you are on. It provides a visual indicator for users, but also maps to accessibility technologies under the hood so they can obtain the same information. Moving up and down in the editor changes the cursor. If you use blocks offline instead of online, it may also update the user interface to provide more advanced information on the code you are writing. Online, however, you are writing code with Parsons problems, which means examples designed for learning.

Blank Blocks

While the tray is a primary way of adding blocks, especially for young users, evidence in the academic literature suggests novices only use blocks for a short time, generally a few weeks [2]. Past this time, learning benefits drop off, compared to text, although the literature is limited in the sense that little longitudinal tracking exists. In the Quorum programming language, however, lines of code are identical to blocks, which means you can turn it on or off. If you like the blocks, just use them as you see fit. If you choose to just use text, you will interact with the code differently but will be learning exactly the same computer science concepts and code. You can think about it kind of like having spellcheck on or off.

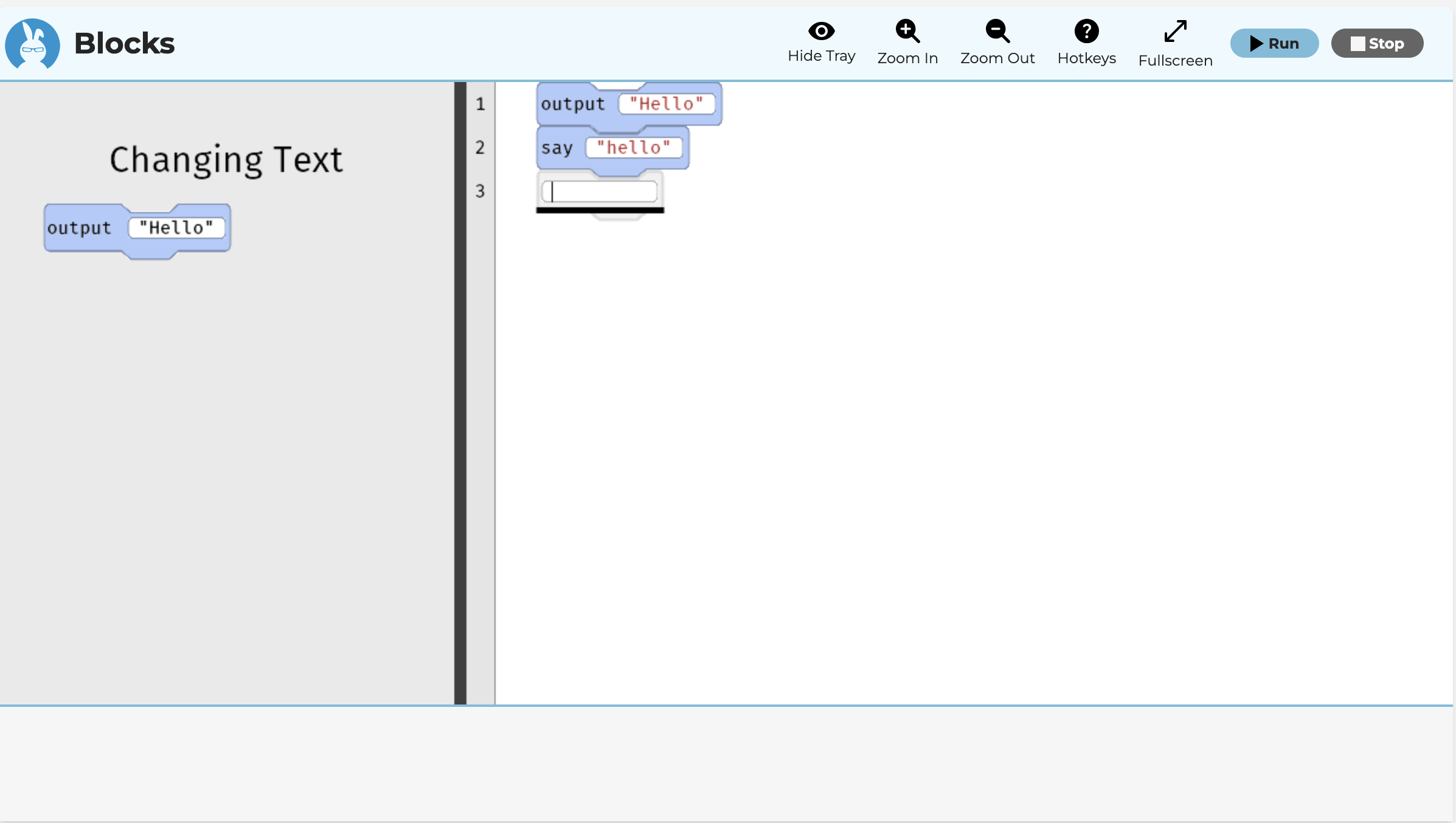

An example of this text and block equivalency is the 'blank block.' Literally, when Quorum Blocks reads the code, it asks itself what the code should look, sound, and feel like. For example, if a normal text editor had a blank line of code, it would be drawn on the screen as a blank line. If the blocks are on, Quorum draws a little box instead. This is true for all possible Quorum code.

For interacting with the environment, while students can use the mouse, similar functionality is available through the keyboard. Blocks can be used forever, for any possible program and the blank blocks help by allowing novices to use the tray or the visual as they see fit. You can add a blank block by pressing the Enter key and can think of it as a temporary place where you can write in text for a short time. In text, the blank block is the same as an empty line of code.

A blank block is white if using the light mode and represents a blank line of code. In an online editor for Quorum Blocks, only light mode is available at the time of this writing. In saying that it is the same as a blank line of code, that is again meant literally. When Quorum reads your source code, if it sees a blank line, it knows that this means a blank block and thus shows a picture of this visually, while also sending information to the operating system for accessibility. If you instead pulled up the code in a text editor, it would visually display it differently but would be the same code under the hood. From this perspective, since blocks are just a visual on top of exactly the same code, both novices and professionals can use the blocks as a choice if they wish. The vertical cursor inside of a blank block allows the user to write a raw line of code, from memory, which provides a form of a text mode without losing all of the benefits of a full switch between a text or blocks style mode. Put another way, if you already know what kind of code you want to write, you can just write it and ignore the blocks without turning them off completely if you choose.

Moving, Changing, and Deleting Code

Traditional block programming environments, if the user makes an error, require the user to drag the code to a trash can or otherwise re-enter it through one mechanism or another. Moving, changing, or adjusting code in the Quorum Blocks editor can be done through a variety of methods.

First, code can be dragged and dropped within the editor.

Second, while the mouse can be used, typical controls like cut, copy, or paste, serve the same function. Thus, pressing CTRL + X, or COMMAND + X, on Mac can also move a block. Third, you can delete a block by pressing the delete key.

Moving the cursor has several common keys, as shown in the following table:

| Command | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Up Arrow | Navigation up, moves to the previous block |

| Down Arrow | Navigation down, moves to the next block |

| Tab | Navigation right, moves to the next part of a block, like the type or variable field, or next block |

| Shift + Tab | Navigation left, moves to the previous part of a block, like the type or variable field, or the end of the previous block |

Comments

Because you can type inside of blank blocks, you can write any line of code. One common problem in coding is that since it is easy to forget what specific lines of code even do, it can be helpful to write a note for yourself. These are called comments. Programming languages always ignore comments, which means they are notes for humans but do not impact your code. Comments are always optional, but can be helpful, and they come in two flavors:

- Single line: Type the characters // and then any text you wish

- Multiple line: Type the characters /* any text you wish, and then ended with */

Because blank blocks are aware of comments, typing the first two characters of comments will automatically convert them into comment blocks for you. As such, if you remember the two slash characters, //, this is often good enough to write a quick note for yourself. A good rule of thumb with comments is balance. Sometimes it is helpful to jot a quick note for a complicated section of code, but commenting every line would be overkill. Finding the right balance is a bit subjective.

Screen Readers

Screen reading technologies and Braille devices can be used with the blocks. Such devices read the corresponding line, similar to a text editor, and provide additional context clues that were designed based on academic investigations [3, 4], then modified based on real-world observational studies [5]. Screen reader users use the same commands as every other user.

To provide some hints on what screen readers say, it is important to know that different readers do provide somewhat different experiences. For example, NVDA, JAWS, and Voice Over say different things in part because every screen reader manufacturer gets to choose the user experience.

Past these navigation systems, there are a host of other navigation commands available. These are not terribly useful at this point, at least until you get to multi-line blocks, but they are documented here for completeness.

| Command | Purpose |

|---|---|

| COMMAND + SHIFT + H or CTRL + SHIFT + H | Smart Navigation up, which jumps to the previous action in a long program |

| COMMAND + SHIFT + H or CTRL + SHIFT + N | Smart Navigation down, which jumps to the next action in a long program |

| COMMAND + SHIFT + H or CTRL + SHIFT + B | Smart Navigation left, which jumps up the current scope |

| COMMAND + SHIFT + H or CTRL + SHIFT + M | Smart Navigation right, which jumps to the next scope |

Variables and Text

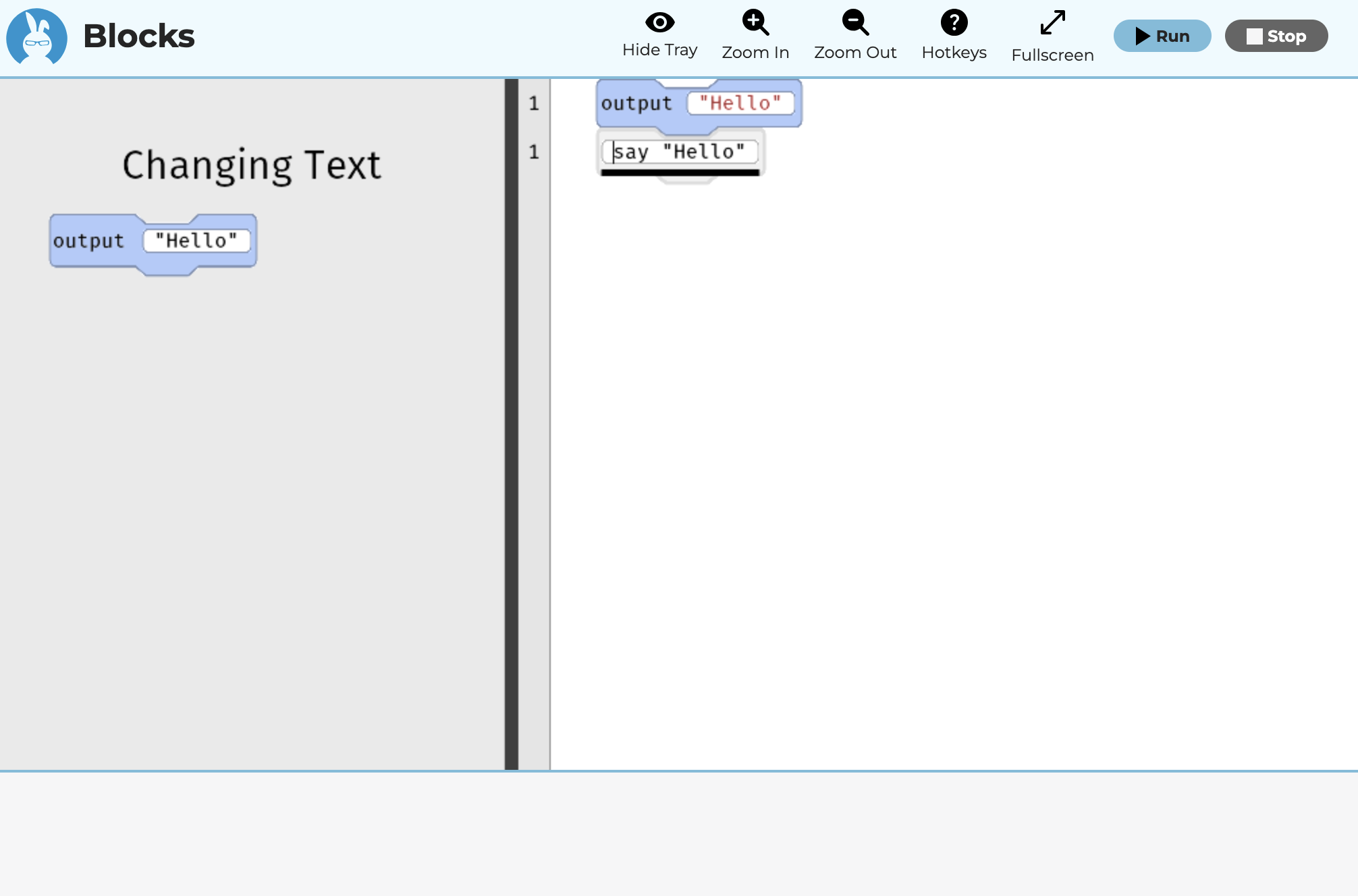

Programming often involves storing information and this is typically done in what are called variables. At a basic level, a variable is a place in the computer's memory where information is stored and a type is which kind of variable it is. In this context, there are four basic types: integer, number, boolean, or text. In this lesson, you will discuss only text and booleans and in the next you will discuss integer and number. While you have already discussed text, what is new here is placing the text in a variable. Here is an example of a text variable that is later output.

Breaking this down, a text variable is a set of characters, numbers, or symbols between double quotes. Text can be anything, so the word hi, your name, a large number, or anything else. It might also be the answer to a question, like the secret code on your luggage or the meaning of life.

Text Operators

Breaking this down, a text variable is a set of characters, numbers, or symbols between double quotes. Text can be anything, so the word hi, your name, a large number, or anything else. It might also be the answer to a question, like the secret code on your luggage or the meaning of life.

Text values only use one operator, which is the plus symbol (+). When used for text, the plus symbol performs what we again use the strange word concatenation in computer science. In other words, it adds one piece of text to the end of another. For example, "hello " + "world" would produce 'hello world.'

text greetings = "Hi " + " there!"This can be output from a concatenated variable as so:

text greetings = "Hi " + " there!"

output greetingsThis code combines the two pieces of text into one, and stores it in the variable greetings. On the next line, it then retrieves the value of greetings and outputs it to the screen. One other aspect of text that is useful is that calculations can be made on the value. In fact, entire fields of study in computer science relate to processing text in special ways. For example, every programming language is, itself, just a really fancy text processing system.

If you run a program, it will still output or say the value of your text, but it will do that by looking up what the value of the variable is in memory. When online, you can run your program from the Run menu by selecting the Run option, or by clicking the blue 'run' button on the toolbar, or by using the hotkey (ALT + SHIFT + R on Windows and Ctrl+SHIFT+R on Mac). When you run the program, it should output the value of the variable. In a screen reading or Braille device, the output is also placed on the page, which means it can be accessed both visually and non-visually.

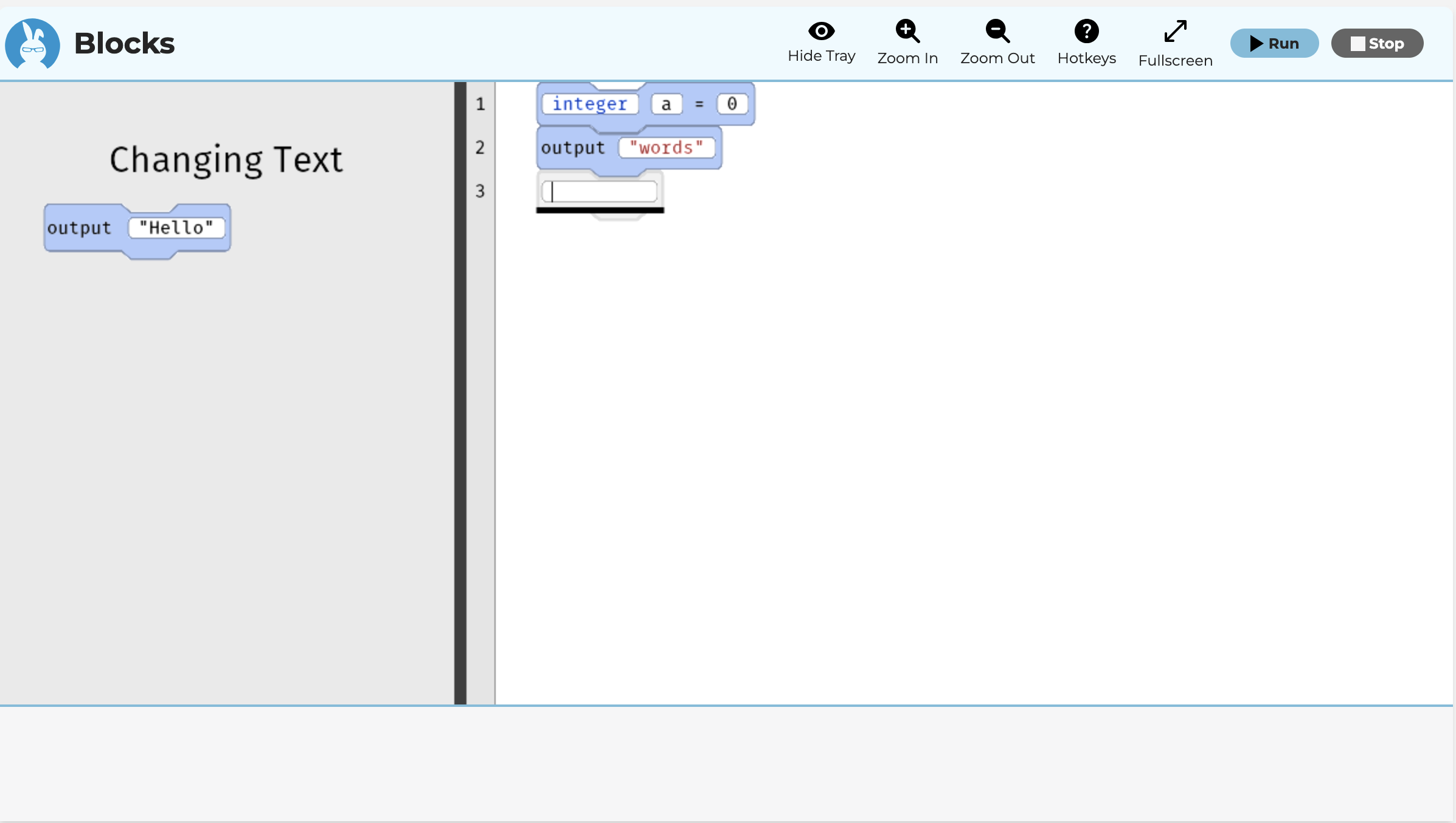

Boolean Variables

While text variables allow you to control characters, numbers, or symbols, booleans have a different purpose. They store variables that are true or false. This may sound limiting and is, on purpose. Variables work similarly to text in that they store information, but they are set differently. Here is an example of making a boolean variable that is true and outputting it to the screen:

boolean a = true

output aThe code here works similarly to before. The value of true is somehow placed into the computer's memory inside of the variable a. How this is done is complex and outside the scope of this lesson, but is sort of like putting a 1 or a 0 at a specific spot in memory. The second line retrieves the value from the variable a and puts it on the screen.

Boolean Operators

Booleans support more operators than text values do. You can use comparison operators on integers and numbers, which will be discussed later. These are equals (=), less than (<), greater than (>), less than or equal to (<=), greater than or equal to (>=), and not equal (not=). These operations produce boolean values. For example, 5 < 6 produces the boolean value true.

Boolean values also use equal (=) and not equal (not=) operators. They can also use the logical operators and and or to combine values. The and operator produces the boolean value true only if both the left and right value are also true, or produces false if either of them are false. The or operator produces the boolean value true if at least one of the two values are true, and only produces false if both values are false. The concept is similar to the concept of a truth table.

Booleans also have a special operator, called not. Unlike the other operators discussed here, not only takes one value, not two. The not operator flips the value of true or false. For example, not true produces false, and not false produces true.

boolean myBooleanValue = true or falseValid and Invalid Variable Names

In order to make your output statement use your variable, you have to give it a name. In big programs, there are often many variables, so giving them meaningful names that represent the kind of purpose they hold can be helpful to human readers. A variable name can be almost anything, but there a few rules:

- Variable names must start with a letter.

- A name can be made of lowercase letters, uppercase letters, numbers, and the underscore symbol: _.

- Names cannot contain spaces or other special characters.

- While quirky, variables cannot end with the underscore character

Citations

- J. Nathan Matias, Sayamindu Dasgupta, and Benjamin Mako Hill. 2016. Skill Progression in Scratch Revisited. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’16). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1486–1490. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036. 2858349

- David Weintrop. 2019. Block-Based Programming in Computer Science Education. Commun. ACM 62, 8 (jul 2019), 22–25. https://doi.org/10.1145/3341221

- Catherine M. Baker, Lauren R. Milne, and Richard E. Ladner. 2015. StructJumper: A Tool to Help Blind Programmers Navigate and Understand the Structure of Code. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Seoul, Republic of Korea) (CHI ’15). Association for Computing Machin- ery, New York, NY, USA, 3043–3052. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702589

- Ameer Armaly, Paige Rodeghero, and Collin McMillan. 2018. A Comparison of Program Comprehension Strategies by Blind and Sighted Programmers. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Software Engineering (Gothen- burg, Sweden) (ICSE ’18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 788. https://doi.org/10.1145/3180155.3182544

- Andreas Stefik, William Allee, Gabriel Contreras, Timothy Kluthe, Alex Hoffman, Brianna Blaser, and Richard Ladner. 2024. Accessible to Whom? Bringing Accessibility to Blocks. In Proceedings of the 55th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1 (SIGCSE 2024). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1286–1292. https://doi.org/10.1145/3626252.3630770

Engage

In this first part of the lesson, you will continue using Parsons problems. This time, you will focus on the three big ideas from this lesson, which are: Blank blocks and comments, Text primitives, and Boolean primitives.

Like before, the broad idea behind problems like these is to limit the number of programming options while learning, emphasizing where lines of code go in a program. New to this lesson, however, is the concept of making mistakes. In some of the Parsons problems here you will be placing code into the right spot. In other types of problems, you will be fixing an issue.

Directions

In this case, like before there are three sets of Parsons' problems. The first, on blank blocks and comments, is optional. The second and third, on text and booleans, however, are extremely crucial concepts to understand in computer science. They are foundational to nearly any program you want to write in the future and solving each problem is highly recommended. In each case, you can drag and drop, use the keyboard, or even just write in the editor the solution to the problem and run the code. As a reminder, the hotkey to run the code is ALT + SHIFT + R on Windows and CTRL + SHIFT + R on Mac.

Parsons Problems

Wrap up

Perhaps the most crucial concepts to understand in this lesson are the primitive types of text and boolean. Text values store characters, numbers, and special symbols in between double quotes. Booleans store true or false and have a variety of operators associated with them like and, or, and not. Discuss as a group the differences between the two types. Focus on how they are represented in code and what they mean in the computer.

Next Tutorial

In the next tutorial, we will discuss Integers and Numbers Online, which describes how to manage integer and number variables.